Becoming A Trauma Responsive School

Becoming a trauma responsive school is a multiyear process that requires improvements on all levels. Sometimes they are small adjustments, other times they are whole paradigm shifts. Change can be managed by considering whether it is a technical or an adaptive change.

A technical change is one where the systems and structures can be put in place and functionally the change can happen with little or no mindset shift. An adaptive change requires a mindset shift in order to institute the change. Identifying whether a change is technical or adaptive can help inform the work.

Technical changes are adjustments that are made with clear and easy to learn implementation steps, and require change in a single process, routine, or structure. Technical changes can often be mandated through a decision made by one person with the appropriate authority. Adaptive changes are more difficult to implement and often require simultaneous change in several areas across the organization. Adaptive changes are especially challenging because they depend on changes in values, beliefs, and relationships, and often people resist acknowledging the problems that indicate a need for an adaptive change. Adaptive changes take time to fully realize because they begin as experiments that must be tested and evolved with new discoveries.

Ideally, technical changes would occur with buy-in from staff, but school administrators may need to set school-wide priorities for technical change while providing staff with support to ensure that buy-in follows. For adaptive change to be successful it is critical that buy-in comes first to ensure that the changes are implemented with fidelity.

TREP FOCUS AREAS

1. Prevention and management of secondary traumatic stress is foundational because learning is best accomplished in the context of caring teacher-student relationships. The stronger the relationship, the more the educator is at-risk for being negatively affected by the child’s traumatic experiences.

2. Mindfulness for all practiced by adults and students throughout the building throughout the day.

3. Physical safety, emotional safety, and psychological safety is a must for adults and students to have a developmentally supportive learning environment.

4. Strong relationships for all among school staff (administrators, teachers, custodial and cafeteria staff, bus drivers, security or resource officers, classroom aides, interventionists), and with students and their families.

5. SEL integrated into core curriculum and instruction that directly teaches social and emotional skills in all subjects through the content, learning activities, monitoring and assessment, and artifacts students produce.

CONTINUUM OF CHANGE

Becoming a trauma responsive school is a multi-year process that starts with professional development and coaching to build staff awareness of trauma and capacity to utilize trauma responsive practices.

All Staff Capacity Building

Shifts In Mindsets And Practices

Practices Strong Throughout School

Trauma Responsive School

Trauma training is institutionalized for all staff.

Coaching to facilitate successful implementation of new knowledge and practices

Supporting staff awareness and management of secondary traumatic stress

Recognize signs and symptoms of traumatic stress.

Mindfulness in all classrooms to reduce dysregulation.

Utilization of practices that create safety and build relationships with dysregulated students.

Trauma responsive practices are considered routine and expected.

At least 75% of staff are utilizing trauma responsive practices and students show improved outcomes.

Institutionalized policies and systems that facilitate the sustainability of trauma responsive practices.

Continued assessment of social, emotional, and academic outcomes for improvement of trauma responsive practices.

MINDFULNESS FOR ALL

Mindfulness is the practice of training ourselves to be fully present and aware of where we are, how we are feeling, and what we are doing in the present moment. When used in schools it is a practice that can improve educational outcomes by teaching strategies that calm the body’s physiological responses to stress and focus the mind. The goal of mindfulness practice is two-fold: first, to build cognitive, emotional, and behavioral self-regulation, and second, to build necessary stress management skills that students can call upon in their daily lives.

Mindfulness is a practice that can be implemented school-wide to improve outcomes for both teachers and students. By building brief moments of dedicated time for easy-to-learn mindfulness practices into school routines, students and teachers become more calm, focused, and responsive, while also experiencing less stress and anxiety. Mindfulness builds cognitive and emotional self-regulation, and by doing so, also builds behavioral self-regulation.

School may be the one place where some students regularly experience what calm feels like, and teachers may be the primary adults who teach them the self-regulation skills needed to succeed in life. Because stress is contagious, student self-regulation begins with educator self-regulation; by ensuring that we remain calm in our responses to student dysregulation we reduce the likelihood of escalation and model to students how we want them to behave.

Mindfulness can be used in three strategic ways in the classroom

A daily practice done during predictable times of the day when students need help bringing down their level of arousal and focusing their thoughts on the learning that is happening in the classroom, such as when students first arrive at school, after lunch, and after recess. During daily practice is when students are best able to build mindfulness skills.

Planned brief mindfulness breaks that can be used strategically during extended academic activities. Some call these brain breaks, which are short breaks to the tedium and lack of focus that can result from forcing one’s self to concentrate on one thing for too long.

Mindfulness practices can also be used as a supportive response to unpredicted stressors, either with the whole class or with individual students. When events happen that make students distressed (anxious, fearful, angry, or sad) you can help students to remember the skills learned in the regular mindfulness practice to help bring themselves into a state of calm.

MULTILEVEL SAFETY

When a child’s brain and body are constantly activated by stress, they develop a heightened level of negative reactivity to everyday events. To counter this and ensure that children’s brains and bodies are functioning in ways that are conducive to learning, children need to trust that their schools and classrooms are safe spaces where they can reduce their hyper vigilant focus on identifying threats and direct their attention to learning.

PHYSICAL SAFETY is feeling protected from violence and threats of violence from peers, staff, and any other member of the school community

Physical safety can be threatened by aggressive and profane statements, a kick in the shins, a punch in the shoulder, and physical fights. Teachers must respond to each occurrence, be firm about their non-acceptance, model and teach appropriate ways of interpersonal communication and interaction, and close with restorative justice practices to ensure that feelings of safety are re-established. Student safety can also be threatened by the physical and sexual actions of adults at school; students need to know that reports of such actions will be believed and investigated.

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY is feeling protected from derogatory statements that negatively affect one's sense of self

There will be times when students will misbehave and need to be disciplined, and during those disciplinary interactions they need to be protected from derogatory statements that negatively affect one’s sense of self. When children display problem behavior that is rooted in their immature attempts to gain a sense of safety by exerting inappropriate control at inappropriate times they are often responded to with punitive discipline. This can lead to a cycle of increased distress that is exhibited through more problem behavior. What children and youth learn from these interactions is how to distrust and avoid adults.

EMOTIONAL SAFETY is feeling protected, supported and enabled to take learning risks, make mistakes, and fail without feeling like a failure

Students need to believe that their classrooms are spaces where they will be emotionally protected, supported, and enabled to take learning risks, make mistakes, and fail without feeling like a failure. Emotional safety can be achieved through validation. Validation communicates value, self-worth, and affirmation. The validating classroom cultivates trust, respect, and empowerment and instills confidence in students to take risks with their learning.

STRONG RELATIONSHIPS FOR ALL

Strong relationships among all teachers and staff across the school building are essential for implementing the changes necessary for a school to become responsive to how trauma disrupts core feelings of trust and attachment. This begins with cultivating an atmosphere of collaboration, transparency, and trust among the adults.

Relationship building with students is a high investment opportunity for teachers because it is the one aspect of students’ school experiences that can be fundamentally changed by a single teacher. Jason Okonofua, a psychology professor who examined the benefits of an intervention to

encourage empathic discipline, stated that, “Just having one better relationship with a teacher at school—just one—can serve as a buffer for all the other struggles and challenges at school.”

The overarching goal of relationship building is to ensure that all students feel a sense of school connectedness and belonging, which includes the belief by students that adults in the school care about their learning as well as about them as individuals. This includes:

-

Feeling respected by the adults in the building

-

Perceiving teachers as supportive and caring

-

Perceiving teachers as understanding of their problems outside of school

-

Believing that discipline is fair

-

Experiencing instruction as connected to their identities and interests

-

Believing that teachers recognize, value, and reward their efforts

Become A Powerful Adder

A Powerful Adder is a teacher mindset toward relationships that can make students feel respected, valued and important in the classroom, even those with the most challenging academic struggles. Verna Price provides a compelling example from having observed how a Powerful Adder engages students in the classroom:

The teacher stood in front of the classroom and asked the whole class a question, an African American boy raised his hand. The teacher called on the boy, he didn’t know the answer and began looking it up in his book. The teacher noticed that he was trying, walked over to his desk, bent over his shoulder and helped him locate the answer. The student found the answer, showed the teacher, then said the answer out loud to the class. The teacher ended by saying ‘thank you’ to the boy, smiled at him, and resumed her position at the front of the classroom.

The Powerful Adder sees:

-

That all students have potential.

-

Is willing to motivate and empower students by providing tools to discover their talents and abilities.

-

Is willing to challenge students to grow and change.

-

Empowers students through their words.

-

Provides students with opportunities to gain new knowledge, skills and understanding.

-

Believes in students and their personal goals and vision.

-

Empowers students to create a vision and goals for their lives.

INTEGRATED SEL PRACTICES

Research indicates that integrating SEL into all aspects of instruction–giving students repeated and connected opportunities to develop their social-emotional competencies throughout the year–yields the greatest gains. This is because all learning that happens at school occurs through interpersonal interactions, between and among students and adults. Therefore, the development of students’ social and emotional skills needs to occur in all areas of the school: classroom, hallway, lunchroom, gym, as well as on the bus to and from school.

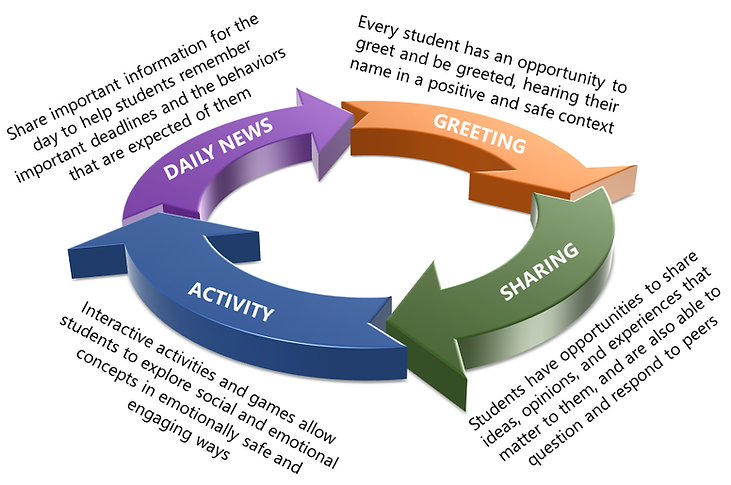

A school can anchor the integration of SEL into routines by providing protected time for SEL in the school day. One way to meet the emotional needs of students coping with trauma is to start the school day with an advisory period. Advisory can also be referred to as a morning or class meeting especially in the younger grades. If done every day this could be as brief as 15 minutes integrated into the start of the first class of the day. If done two to three times a week, a set-aside 30-minute morning advisory can be enough to meet students’ needs.

There are many resources for grade level lesson plans and agendas to make advisory productive for students and teachers. A few web links are included at the end.

EXAMPLE ADVISORY STRUCTURE

Adapted from Crawford’s L. The Advisory Book.

There is no subject for which SEL is irrelevant or tangential. For example, SEL can be integrated into math classes through the content of word problems, having students work collaboratively to complete problem sets, and having class-wide discussions about problems that can be completed using more than one method.

Integrating SEL into curriculum and instruction is a key component of becoming a trauma responsive school. Begin by assessing the current practices, policies, and procedures your school takes to implement SEL for adults as well as students. Many schools use CASEL’s 5 Core Competencies: Self-Awareness, Self-Management, Social Awareness, Relationship Skills, and Responsible Decision Making.

Sample Embedded SEL Math Lesson

When reviewing fractions in a fourth-grade math class, the teacher asks students to solve a problem, come up with multiple ways to demonstrate their solutions, and share with their peers. The teacher then engages students in a discussion to evaluate how well each approach worked in solving the problem.

The following set of teacher practices and student behaviors ensure the successful execution of a lesson employing self-assessment and self-refection teaching practices.

The following math lesson example uses the teaching practice of Self-Assessment and Self-Reflection. In this lesson, the teacher helps students to engage with content in a way that not only builds their understanding of math concepts, but also builds problem solving and communication skills. Mastery of the social and emotional skills will enhance their ability to successfully complete complex math problems. Thus, there are multiple benefits to explicitly teaching SEL during math and allowing time for practice.

Teacher Practices

Student Behaviors

Shares with students the learning goals for each lesson

Understand the goals they are working toward

Asks students to reflect on their personal academic goals (e.g., make connections to the lesson goals)

Actively think about their work as it relates to the learning goals

Provides students with strategies to analyze their work (e.g., performance rubrics, peer reviews)

Monitor their progress toward achieving the learning goal

Creates opportunities for students to monitor and reflect on progress toward learning goals

Identify what they do and do not know against performance standards

Creates opportunities and resources for students to monitor and reflect on their social and emotional skills

Utilize support resources based on what they do and do not know

Strategizes with and supports students to make sure they meet their learning goals

Identify strategies to improve their work and/or behavior

Provides students opportunities to reflect on their thinking and learning processes (e.g., using graphic organizers or journals)

Provide feedback on the strategies used for their learning

MANAGEMENT OF SECONDARY TRAUMATIC STRESS

Over the past 25 years, research has consistently shown that the process of providing care can deplete the caregiver’s emotional resources, and is particularly challenging for those who provide the most empathetic care. Education is a caring profession and learning is best accomplished in the context of caring teacher-student relationships. This relationship is also one of the most powerful tools for promoting recovery from traumatic experiences, and the stronger the teacher-student relationship the more at-risk the educator is for being negatively affected by the child’s traumatic experiences.

Compassion Fatigue

Secondary

Traumatic Stress

Burnout

Vicarious Traumatization

Compassion fatigue is emotional and physical fatigue that you may experience from the stress of working with people who have experienced trauma and suffering. Compassion fatigue often builds up over time.

Secondary traumatic stress is the result of bearing witness (directly or indirectly) to someone’s trauma. You may experience intrusive thoughts, memories or nightmares related to students’ experience with trauma, insomnia, irritability, and angry outbursts.

Vicarious traumatization is the process of cognitive change that occurs from working with people who have experienced trauma. Symptoms may include: a change in your sense of self, developing a negative or anxious world view about safety, trust and control, and changes in spiritual beliefs.

Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious traumatization can build up over time or emerge suddenly. They can be independent from each other or happen at the same time.

Burnout is a state of physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual exhaustion that occurs over time. Symptoms include decreased attendance, lower job performance, diminished feelings of professional accomplishment, and an increase in physical and mental health challenges.

Research has also shown that whole institutions can be negatively affected by traumatic stress. Schools and other institutions are a collective of individuals, and when the individuals within the institution have low levels of mental and emotional health the efficacy of the whole institution is compromised. Susan Bloom uses the term Trauma-Organized Systems to describe negative institutional adaptation to chronic stress in the workplace, which leads to dysfunctional and punitive decision-making, and practices that can often re-traumatize the same people that they are trying to help.

Maintaining your emotional health is essential when caring for children and youth impacted

by trauma. You cannot support someone else until you support yourself first.

The good news is that research also shows how to prevent and manage the negative effects of the psychological and emotional costs of providing care.

Self-care is critical as well as developing healthy in-the-moment strategies for mindfully reflecting on and cognitively reframing negative emotional experiences. The most important piece of new research is that collective-care, which shows how schools can develop systems and structures that minimize the emotional toll and stress associated with educating traumatized students, is also critical.

Emotionally supportive workplaces provide staff with opportunities to individually and collectively reflect on and process negative events and experiences, provide support, space, and time for intentional self-care, provide professional development to help staff develop self-care practices, and facilitate the development of composition satisfaction. Compassion satisfaction is a particularly important buffer against the emotional exhaustion associated with educating traumatized children.

Compassion satisfaction is strengthened when we experience and feel personal efficacy in doing difficult work, and feel a sense of purpose in doing work that is improving the lives of others. For this to happen educators must be supported in developing the tools and skills that enable them to meet students’ needs, and are supported with policies and procedures that do not undermine their individual efforts.

EFFECTIVE AND EFFICIENT BMHT MEETINGS

Schools are one of the primary places where children’s mental health challenges become detectable, and national studies estimate that over 70% of children and adolescents in need of mental health treatment do not receive services. Research shows that to meet these needs it is important for schools to have what we call a Behavior and Mental Health Team (BMHT). The BMHT is the group of professionals tasked with the planning and implementation of school social, emotional, and behavioral health supports. They use data to assess student needs as well as plan, coordinate and evaluate services, and by doing so improve the outcomes for vulnerable students who might otherwise experience exclusionary discipline through suspension and expulsion, grade-level retention, slower learning trajectories, dropout, and a host of negative later life outcomes.

The BMHT coordinate supports and interventions across Tiers 1, 2, and 3. Tier 1, or universal supports, typically refers to services available to all students. Tier 2, or targeted supports, are available to some students identified as needing modest additional services. Tier 3, or individualized services, are intensive one-on-one services for a small percentage of students provided by counseling and clinical staff. Even though schools do not have the resources to fully meet students’ needs for Tier 3 individual therapy, or Tier 2 small-group counselling, by engaging in coordinated Tier 1 trauma responsive educational practices, schools can play a significant role in reducing the primary effects of trauma on students’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning, and the secondary effects of school failure.

By creating a functioning BMHT, high needs schools move from lurching from one student crisis to the next to having a protected meeting time to think and plan proactively for student interventions that go beyond minimizing harm, and a school’s long list of overlapping and sometimes competing interventions, often involving several different programs at each tier, are transformed from stand-alone and disconnected interventions into an integrated and coordinated system of supports.

A strong BMHT team will be comprised of a diversity of professionals who can provide relevant information about various aspect of the lives of students. BMHT members could include:

-

Administrators

-

Teachers

-

Social workers, counselors, psychologists

-

Deans, security

-

Restorative Justice Coordinator

-

Community and contracted mental health provide

The challenge is the scarcity of meeting and planning time relative to the high number of students that need planned support. Though our work with schools we are learning how to make a one-hour weekly meeting work and will share those lessons. At the very least we suggest taking a Solutions Focused Approach to all BMHT meetings.

It is easy for meetings to become focused on lamenting the problems week after week with

little movement toward solutions—the problems are many and the resources are few.

Solutions focused BMHT meetings discuss school-wide, grade-level, or individual student issues, in ways that focus on leaving the meeting with a plan(s) for small incremental changes that can be implemented immediately. The solutions are based on previous/current behaviors/strategies that have led to success for at least one person or area in the school. Thus, the goal is to move forward using existing skills while learning new ones. To implement this approach, one has to move away from unhelpful questions that focus on assigning blame and discussing what is wrong to move toward helpful questions that focus on identifying the desired outcome and the actions necessary to achieve that outcome.

The solution-focused approach is simply a framework and set of questioning tools that informs thinking in an ever forward movement. The FORWARD acronym helps explain the solution-focused approach.

QUESTIONS TO INITIATE AND GUIDE CHANGE

The following questions can help guide planning for change:

-

Is there an issue of harm that must be addressed FIRST in order to do this work?

-

E.g., Are students using violent communication in peer interactions that is psychologically harmful?

-

-

Where is there momentum, energy, or interest already?

-

E.g., What SEL programs are already in place such as Calm Classroom or an advisory?

-

-

Which components can be shifted through a technical change?

-

E.g., Can all staff be requested to begin their 1st period class with a mindfulness practice?

-

-

Which components will necessitate an adaptive change?

-

E.g., Are teachers and staff currently isolated and in silos in their individual work so that collaboration will require a mindset shift to cultivate?

-

-

Is there an adaptive change underway that could support moving into this work?

-

E.g., Is the school already working on a specific positive or restorative discipline practice?

-

-

What current initiatives, partnerships, or efforts align with becoming trauma responsive?

-

E.g., Are you currently working with a community mental health provider, theater or art therapy group, or after school mentoring program that can be broadened and strengthened?

-

How One School Becoming Trauma Responsive

TREP Year 1 = 1 Focus Area

1. MULTILEVEL SAFETY addressing issues of physical aggression between students was the primary focus this year.

TREP Year 2 = 4 Focus Areas

1. MULTILEVEL SAFETY began as technical change in Year 1, continues as an adaptive change.

2. MINDFULNESS FOR ALL was implemented as a technical change strategy that requires it in all classrooms at start of the day, and after lunch, and calming strategy as needed.

3. STRONG RELATIONSHIPS FOR ALL was implemented as an adaptive change strategy that includes focused peer observations, and school-wide teacher-student relationship checks.

4. FOUNDATIONAL SEL PRACTICES were implemented as technical change elements that include Calm Center on each floor and rotating schedule of adult supervision by staff not in the classroom; 3 school wide rules that are defined, described and posted; common practice during transitions, and classes starting with “First 5 Minutes”; classroom rules and expectations posted under the clock; use of pre-corrections. Adaptive change strategies include staff collaboration strategies such as common behavioral expectations by grade-band and collaboration meetings 2 x/ month during grade-band meetings with facilitator.

CITATIONS

A Few Advisory Resources:

Bluestein, J. 2001. Creating Emotionally Safe Schools: A Guide for Educators and Parents. Deerfield Beach, FL: HCI Pub.

CASEL. (2003). Safe and Sound: An Educational Leader’s Guide to Evidence-Based Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Programs. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

Crawford, L. (2008). The Advisory Book. Minneapolis, MN: The Origins Program.

Heifetz, R. A., Linsky, M., & Grashow, A. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Missouri Model (2014). A developmental framework for trauma informed, MO Dept. of Mental Health and Partners (2014).

t's easy.

Price, V. (2006). I Don’t Understand Why My African-American Students Are Not Achieving. In Landsman J. and Lewis, C. W. (Eds.). White Teachers / Diverse Classrooms: A Guide to Building Inclusive Schools, Promoting High Expectations, and Eliminating Racism. Stylus Publishing, VG: Sterling.

Sparks, S. D. (2016). How Feeling Respected Transforms A Student’s Relationship to School. PBS New Hour. Available Online: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/feeling-respected-transforms-student-school

The Tennessee Department of Education (2015). Incorporating Social and Emotional Learning Into Classroom Instruction and Educator Effectiveness. Center on Great Teachers and Leaders.

Tranter, D. & Kerr. D. (2016). Understanding self-regulation: Why stressed students struggle to learn. What works? Research into practice.

Visser, C. & Bodien, G. S. (2019). Moving FORWARD with Solution-Focused Change: A Results-Oriented and Appreciative Way of Making Progress. https://progressiegerichtwerken.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Moving-FORWARD-with-solution-focused-change.pdf

Yoder, N. & Gurke, D. (2017). Social and Emotional Learning Toolkit. SEL Solutions at American Institutes for Research